|

Children's fractures are different than adult fractures in many ways. The unique

anatomy of children's bones leads to fracture patterns not seen in adulthood. The fact that the bones are growing leads to many more considerations both good and bad that the adult orthopedist does not deal with.

First, let's start with the anatomy. The most noticeable difference between adult

and children's bones is that children's bones have growth plates ("physeal plates"), which are located at the ends of the long bones and are responsible for the longitudinal growth of a bone. There is a specific classification for fractures, which

pass through the growth plate.

Children's bones are surrounded by a thick fibrous sheath ("periosteum") which is

responsible for growth in thickness. This periosteum is much thinner in an adult. In the child, the periosteum can impart some stability to a fracture. The

arrangement of the protein making up a child's bone allows the bone to be more plastic; meaning it can bend a lot before it breaks. This also allows for different types of fractures seen in children and not the adult.

Injury to the growth plate can be minor or severe. Often an injury to the growth plate may not be seen on a x-ray, because the cartilage making up the growth plate is not calcified and therefore seems to be a clear space. A minor injury may be diagnosed on the basis of tenderness (tenderness means a specific spot that hurts when pressed by a nasty probing finger) at the growth plate alone. The more severe the injury, the more likely some growth disturbance will arise after the fracture has healed. This is termed a growth plate arrest, which will usually be detected within nine months of the injury if it happens at all.

Having growth plates has some advantages. Fractures in bones that are growing will correct their own shape ("remodel"). Remodeling simply means that a growing bone, which is deformed, will attempt to straighten itself out over time. The closer the fracture is to a growth plate, the more it can remodel. For this reason, we accept some fracture alignments in children that we cannot accept in adults. We always strive to align a fracture perfectly, but we have a little more leeway in the child.

The periosteum of a child's bone is thick. It allows for fast fracture healing because it is very vascular and active. It also can impart some stability to a fracture, which improves healing in a cast. An orthopedist often takes advantage of the periosteum being intact to reduce fractures (reduce the displacement and/or angulation) with greater ease.

Since a child's bones can bend a lot before breaking, different fracture patterns can be seen in children. A toros (toros = knuckle or bump, ie: not the bull torus)

fracture is a term used for a distal radius fracture in which the back cortex is disrupted from a compression injury, while the front cortex is stretched but does

not break. A bump is typically seen. This is a stable injury, treated with a cast for a short time. A buckle fracture is a synonymous term to the

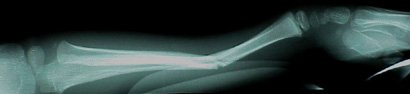

toros fracture. A green stick fracture refers to a fracture where one side of the bone breaks from a distracting force while

the other side bends but stays intact (as what happens to a green, that is young, stick when you try to break it). These fractures often need to be reduced

manually and the intact cortex is often cracked a bit to achieve a better reduction.

A green stick fracture refers to a fracture where one side of the bone breaks from a distracting force while

the other side bends but stays intact (as what happens to a green, that is young, stick when you try to break it). These fractures often need to be reduced

manually and the intact cortex is often cracked a bit to achieve a better reduction.

Plastic deformation refers to the bone bending but remaining intact. This injury often will require a reduction with a slow unbending of the bone or a controlled

completion of the fracture in order to better align it.

Generally speaking, a majority of pediatric fractures are satisfactorily treated in a cast. Often the

fracture is first placed in a splint before the cast. The splint will allow for swelling, which may occur, in the first few days following the injury. When the swelling is decreased, a carefully shaped cast is

placed to hold the fracture in alignment.

Generally speaking, a majority of pediatric fractures are satisfactorily treated in a cast. Often the

fracture is first placed in a splint before the cast. The splint will allow for swelling, which may occur, in the first few days following the injury. When the swelling is decreased, a carefully shaped cast is

placed to hold the fracture in alignment.

Danger Signs:

You can recognize if a splint or a cast is too tight by looking for following findings. The most important

and often the earliest finding is an increase in pain, which may be described as a throbbing pain. The

pain often increases further if you wiggle the patient's fingers or toes. The child may also complain of a numb feeling in his or her fingers or toes. A late sign

would be if the fingers or toes turn white, signaling they have lost their circulation. The thing to do is contact your child's doctor. The splint or cast may need to be opened to allow for the swelling. This will almost always relieve the pressure and

alleviate the pain. In some rare cases, additional care may be needed.

Some Need Anesthesia :

Some fractures are simply too tricky to put in place without severe pain. Add to that, muscle spasm which locks in the shortening. Often, especially if the child is

not in the best circumstances for anesthesia, local anesthesia can be used. This is the same stuff the dentist uses.

Some Need Surgery :

Bones can fracture with barbed edges that catch on

other tissue, or have surfaces so fragmented that no firm surface exists to hold a stable repositioning. There are also key chunks of bone with muscle attachments, that when pulled off spin around 180 degrees from the pull

of the muscle. No external fiddling will get them back.

Fractures, which are likely to require surgery, include:

fractures extending into a joint,

fractures displacing a growth plate,

pathologic fractures (fractures through abnormal bone),

fractures that just won't reduce or stay put, and

open fractures (those exposed by lacerated skin).

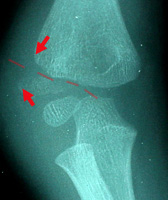

Osteo-chondritis dessicans (a fragmentation of bone with cartilage) is a condition in which the large cartilage area at

the joint which later which later transforms to the substance called bone, does so irregularly. Instead of an expanding uniform transition of cartilage, small islands of bone appear.

They seem disconnected. In fact they are connected, but within the larger cartilage structure, like grapes floating in Jello.

Osteo-chondritis dessicans (a fragmentation of bone with cartilage) is a condition in which the large cartilage area at

the joint which later which later transforms to the substance called bone, does so irregularly. Instead of an expanding uniform transition of cartilage, small islands of bone appear.

They seem disconnected. In fact they are connected, but within the larger cartilage structure, like grapes floating in Jello.

However, shearing stress can occasionally split the softer cartilage and pull off such an island of bone - as a flap (shown) or as a loose body. The x-ray might not be able to tell whether the bone hunk is actually a free or partially attached piece.

If the surrounding cartilage is not split, then eventually the bone piece will link up with the rest of the bone as cartilage continues to transform. This is especially true if the growth plates are open. But if the piece is free or split open, then a problem exists which needs a surgeon to deal with it. In the past, arthrograms (fluid contrast injected into the joint) could see the tracer material seeping deep to the joint surface indicating a fragmentation of the cartilage. MRI MIGHT be able to discriminate. It depends on the size of the chunk and of the joint. Any articular joint may have this happen. The most common ones to come to intervention are the knee, elbow, ankle and occasionally - the hip

Surgery is tailored to the specific  requirements of the fracture. Elbow fractures are

the ones most likely to cause trouble in every category, and to require pin fixation.

requirements of the fracture. Elbow fractures are

the ones most likely to cause trouble in every category, and to require pin fixation.